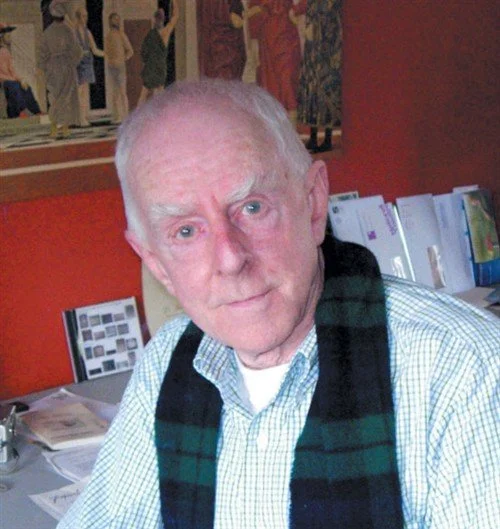

Owen Hatherley remembers Christopher Woodward (1938-2022)

The text below is published in memory of Christopher Woodward, the architect and writer whose seminal book Guide to the Architecture of London, which he co-wrote with Edward Jones, has played a key role informing the curation of Open House Festival for decades. A much-abridged version of this text first ran in the Guardian newspaper in 2017, but with the permission of its author, Owen Hatherley we are pleased to publish the full original piece as a tribute to Christopher.

There is only one Guide to the Architecture of London

By Owen Hatherley

There are many guides to the architecture of London, but there is only one Guide to the Architecture of London. Since its first publication in 1983, the regularly updated book has been utterly definitive, superseding dozens of other instantly forgotten gazetteers. It is, however, rather heavy – increasingly so, with its latest update, in 2013, a brick-sized thing more useful for violence than urban exploration. Happily, the book now exists as an App, developed with the Architecture Foundation. In order to test it, I met the Guide's authors, the septuagenarian architects Edward Jones and Christopher Woodward, and tried to see if the app can offer the same insights into the city that the book does.

We meet in Air Street development, the former Regent Palace Hotel, designed by Henry Tanner in 1914, in a fluffy, tile-clad Edwardian baroque style. Jones and Woodward picked this because the former, in his capacity as co-director of the long-established firm Dixon Jones, worked on its transformation into Qudarant 3, a mixed use apartment/retail complex. 'A good simulacrum', in Woodward's words. The faience facades of Air Street sit just at the 'border' between Soho and Regent Street. He describes Soho as being squeezed between two landlords, 'like one of those Syrian towns Isis is reduced to fighting over block by block'. But at the same time, they're keen to point out the qualities of the new building, which Jones describes as taking a 'dead frontage' and turning from 'one block' into 'several little pieces' in red, blue and white faience, for which they hired the original building's Lancastrian tile-makers, Shaws of Darwen.

Being a respected practitioner himself, Edward has to measure his words, but Christopher has no such problems. Both former AA students – Christopher from 1957, Edward from 1958. They both worked on Milton Keynes in the 1970s, Jones on housing, Woodward on the recently listed shopping centre. The new town's grid is deployed in the Guide, with London divided evenly into squares, a radically abstracting gesture in this messy metropolis. Both writers insist this was necessary, describing the conventional division of London into villages and districts as 'just marketing'. The guide was originally commissioned from the two as a guide to 'modern London', but when they insisted that modern London began in the 18th century, with the classical laying out of the Great Estates, they were given permission to take the city's entire history. But a classical, rationalist, progressive philosophy runs through the book, one that finds the likes of Victorian Gothic and Zaha Hadid deeply suspicious.

We decided to pick Soho, partly because of Edward's work here but also because it was one of the first places in London to be treated like a continental capital, used for strolling, promenading and for formerly un-English forms of urbane enjoyment. 'As a student, I lived in Percy Street', just on the other side of Oxford Street in Fitzrovia, where the AA owned residences, says Edward. 'Maltese gangsters with guns used to shoot each other at lunchtime'. Christopher remembers 'the first Cappuccino machine in Soho, and the first tables on the pavement in Percy Street'. Both lament the absence of St Martins College from Soho, its building now an appendage to a bookshop; but it is of course in the Guide and the App, its classicised modernism exactly the sort of thing that Jones and Woodward like.

On the tables outside Quadrant 3, we consult the app. First you see a map, which you can enlarge, and find little pins pointing to buildings, with photographs appended – among other things it shows the overwhelming dominance of North London in the book, but it also breaks up its rationalist grid. Below the map is an icon for sorting, according to date and typology, various lists, and then an icon that brings up one of Jones and Woodward's razor-sharp historico-critical descriptions. So at Air Street, the app first offers us the nearby County Fire Office by Sir Reginald Blomfield, then suggests to us nearby works by the same architect as the Regents Palace Hotel, Henry Tanner (he designed the grand Edwardian frontages of Oxford Circus), and of course gives us directions to each.

Exploiting the fact that the app can organise London chronologically, we ask it first to take us to the earliest parts of Soho, when it was laid out in the 17th century as a grid around two squares, Golden Square and Soho Square. On the way, we try to find some of the Georgian Soho, but the App directs us instead to Fribourg's, a well-preserved shop front in Haymarket. Ignoring that, we try to find the piquant classical church of St Anne's, with its elaborate anti-dogging fences, but are surprised to find it is actually in the 1800-1900 section – we had assumed the app was broken. 'It is rather slow', warns Christopher. Walking down Brewer Street, Christopher is surprised that the moderne car park (in neither Guide nor App) survives and has not 'had its value released'. Walking down Old Compton Street, Christopher notes the increasing absence of 'porn shops' and gay bars, but then asserts that 'none of this is to be particularly regretted, because of the internet'. Regrettably, none of these observations can fit into the Guide/App, but they give some sense of its tone.

At Soho Square, we admire St Patrick's, with its tall redbrick tower; the App, and the two writers, suggest we drop in. A service is in progress, beneath a rather fabulous 'provincial Italian' baroque vault. After that, we ask the app to take us to 'Post-2000', and it directs us to Richard Rogers's-2002 Broadwick House. Unexpectedly, neither is especially impressed by the building today, and are more sympathetic to the council tower block behind it. Christopher blames the Caffe Nero on Old Compton Street on Lord Rogers ('and Tony Blair'), and notes that Broadwick House has 'one of those wavy roofs', thankfully no longer fashionable. Soho was the birthplace of this would-be-continental aesthetic, with the mix of the sex industry, pop and media, and an established Italian community. Christopher recalls the New Left Review's old Cafe Partisan, and states that 'it had plywood furniture, that was its appeal'.

Ending back at Quadrant 3, Edward points out the flats at the sharp, florid corner of the block – 'Al Gore lives there, which we're very pleased about'. Christopher and Edward discuss how the Conservative administration of Westminster Council has managed to preserve the place's fabric far better than the City of London, under the planning rule of 'that charlatan, Peter Rees', but are sad that this conservationism coexists with a reactionary approach to the sort of alternative lifestyles Soho has been built on since the 50s. In a way, the building that we sat outside was an example of this very process, though Edward points to the cheap £10 dinners of the Zedel restaurant downstairs, with their deeply 'period' art deco interiors by Oliver Bernard, the restoration of which he's keen to credit to the architect Donald Insall.

'The immediacy of the app gives a journalist's view' rather than a historian’s one, worries Edward – the Guide has always had the ambition to be a first draft of History, not just a guide to what is fashionable. The Architecture Foundation are keen that the two update the app with new buildings – they have no intention of producing another edition of the Guide, finding the 2013 update exhausting - so 20 buildings are in the App that aren't in the guide. Christopher tells me that the app features O'Donnell and Tuomey's Photographers Gallery, finished in 2014, but Edward disagrees. 'I wrote the entry, but you wouldn't photograph it because you didn't think it was good enough!' True enough, it doesn't feature on the App. Not just anything gets to go in. 'I don't want to turn this into a crowdsourcing operation', Christopher says. 'We want to keep editorial control'.