John Morden Centre by Mæ Architects wins the 2023 Stirling Prize

An ambitious community hub for Morden College in Greenwich has triumphed in Britain’s most prestigious award for new buildings. Our director, Phineas Harper, reviews the building

Britain is a bad place to grow old. Thirteen years of austerity has crippled the UK’s once-strong social and health infrastructure leaving vulnerable people, in particular older communities, at severe risk. Stroke victims are on average now waiting more than 90 minutes for ambulances. The number of patients stuck in emergency rooms without treatment for more than 12 hours has reached an all time high. In the week the email commissioning me to write this review landed, 2,156 more people died than in previous years – many of them older citizens whose lives could have been saved with speedier better-funded medical care.

Nearly three million Brits aged over 50 are unable to access care at all. Often this means struggling to go to the toilet, eat, get dressed or wash. Later life should be a chance to explore deep passions enriched by decades of experience and wisdom, liberated from the grind of work or parenthood – but for many, the UK offers only a hard, scary and expensive decline into neglect.

Yet a few architects, empowered by ambitious clients, are determined to change this gloomy story. Mæ, a South London practice best known for its accomplished housing schemes, is one of a discernable generation of studios restoring dignity and generosity to the often emaciated sector of sterile retirement architecture. In 2020 Mæ completed a complex of 39 flats in Westminster with a cloistered courtyard garden, roof terrace and steam rooms for retirees hoping to grow old in the heart of the city. The flats don’t come cheap but are built with the capacity to allow live-in care as needs change and challenge out of date stereotypes about old people’s tastes with a refreshingly urban character.

Building on the success of their Westminster scheme, Mæ have now completed the John Morden Centre, a cluster of brick-clad cross-laminated timber (CLT) buildings acting as a social and care hub for Modern College in Blackheath. Founded over 300 years ago, the South East London college is a unique institution, providing later life accommodation targeted specifically at residents who have led adventurous careers but who have since fallen on hard times. This peculiar criteria means the college is populated by worldly and creative residents many of whom were leaders in their fields in middle age – a potent community with whom to test ideas for the future of British retirement facilities.

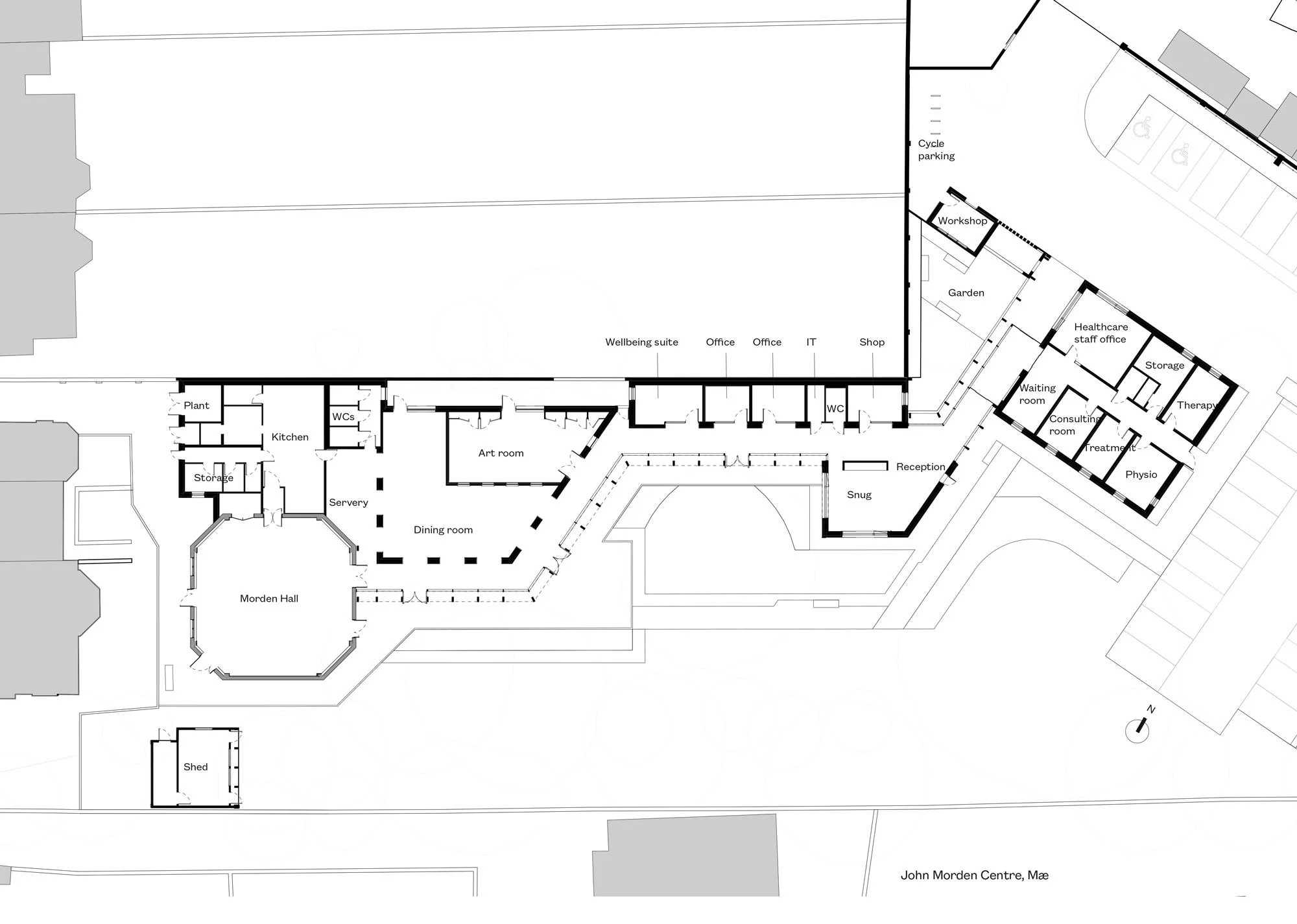

Plan of the new John Morden Centre

The original college was built in 1695 by Edward Strong, master mason of Christopher Wren, taking the form of a cloister of classical brick arms houses with a chapel and ancillary buildings linked by an axial colonnade. Over the centuries, additional accommodation has appeared around the grounds creating a substantial campus with charming landscaped gardens. Approaching on foot from the adjacent heath, the old college appears like a grand country house cresting a gentle hill with Mæ’s additions set slightly to the south.

British planning officers are easily seduced by brick facades, often insisting that new steel, timber and concrete buildings are clad in ornamental bricks or brick slips, frequently yielding disappointing results. But for the John Morden Centre, Mæ have matched the colour and course of the brick skin that wraps their scheme to the original alms houses, cladding the new building in a single leaf version of flemish bond with cut headers. The result is assuredly contemporary with just enough hooks back to Wren and Strong’s work, such as prominent chimney-like brick ventilation turrets, to feel at home.

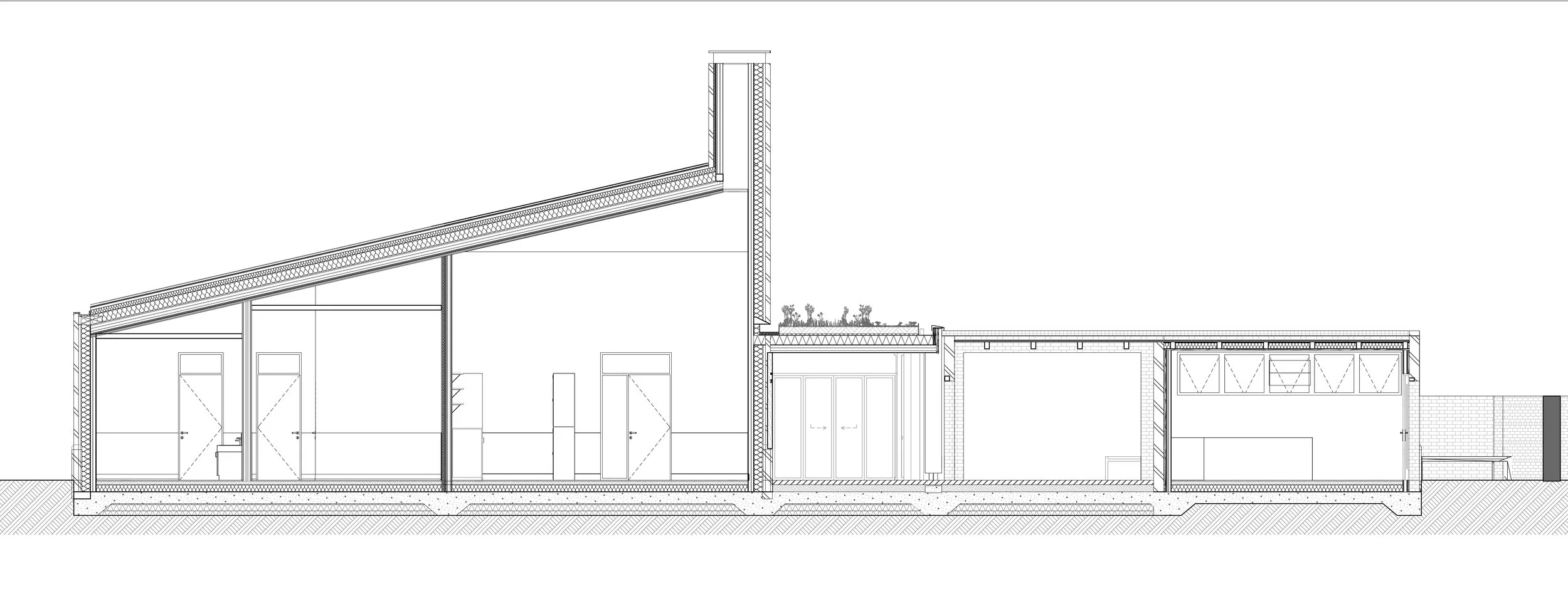

Inside are treatment rooms, offices, art and event spaces, a hair salon, nail bar and a large cafe. Riffing off the original 17th century cloisters, Mæ have organised the centre’s facilities within CLT pavilions hung off a zig-zagging colonnade that opens out onto small terraces and gardens designed with landscape architects J&L Gibbons. “It’s like a giant balsa wood model” explains architect Alex Ely, “the walls and roof are structural timber panels which are prefabricated in the factory then brought together on site.”

Speedy to construct and relatively low carbon, the angular CLT pavilions create pyramid-like volumes that make a lofty and welcome reprieve from the low suspended ceilings of so many institutional healthcare facilities. Except for the extremely reasonable price of a cup of coffee, the chic cafe feels more like it is part of a spa hotel chain than a residential care home – which is exactly the point.

Less successful are some of the decor choices by Scott-Masson, an interior design firm based in Poundbury (the kitsch neotraditional dormitory town built by King Charles III in Dorset), which were not part of Mæ’s original proposals. Though mercifully absent from the principle photography, the addition of cloying wallpaper, prissy light fittings and some florid furniture has detracted from the cliche-busting maturity of Mæ’s designs and seemingly alienated some residents.

Section drawing through the John Morden Centre

Though the centre is a massive upgrade from the portacabins which preceded it, some residents feel that management have used the project to squeeze out messy activities like painting and carpentry which used to thrive in the creative milieu of the college community. There are paintings sitting on easels in the gorgeous light-filled art room for example, but they are clearly for display purposes while the resident who actually paints most prolifically has been relegated to a rather gloomy and chilly out building. In part thanks to Scott-Masson’s prettifying additions, the centre feels pitched for neat self-contained activities with perfect spaces for knitting, pilates, music and manicures (scores of nail varnish bottles line the in-house hair salon) but I can see why the more expressive residents feel left out. Even somewhere as forward-thinking as Modern College, the question of how to continuously balance the needs of everyone, including cantankerous old timers, is a constant challenge.

Ultimately Mæ’s John Morden Centre is a remarkable facility, leagues ahead of what the vast majority of British people get access to in later life. It is an inspiring place which has a great deal to teach this country about how, with the right investment, good architecture can support dignity, care and sociability in later life. “I’ve never worked anywhere like it” the receptionist tells me almost unprompted “everyone is so lovely, it doesn’t feel like work” – that sounds like a good place to grow old to me.

A version of this review was originally published in Dutch by de Architect.

All photography by Jim Stephenson.